It’s Hard To Change The Keys To The Internet And It Involves Destroying HSM’s

The root of the DNS tree has been using DNSSEC to protect the zone content since 2010. DNSSEC is simply a mechanism to provide cryptographic signatures alongside DNS records that can be validated, i.e. prove the answer is correct and has not been tampered with. To learn more about why DNSSEC is important, you can read our earlier blog post.

Today, the root zone is signed with a 2048 bit RSA “Trust Anchor” key. This key is used to sign further keys and is used to establish the Chain of trust that exists in the public DNS at the moment.

With access to this root Trust Anchor, it would be possible to re-sign the DNS tree and tamper with the content of DNS records on any domain, implementing a man-in-the-middle DNS attack… without causing recursors and resolvers to consider the data invalid.

As explained in this blog the key is very well protected with eye scanners and fingerprint readers and fire-breathing dragons patrolling the gate (okay, maybe not dragons). Operationally though, the root zone uses two different keys, the mentioned Trust Anchor key (that is called the Key Signing Key or KSK for short) and the Zone Signing Key (ZSK).

The ZSK (Zone Signing Key) is used to generate signatures for all of the Resource Records (RRs) in a zone.

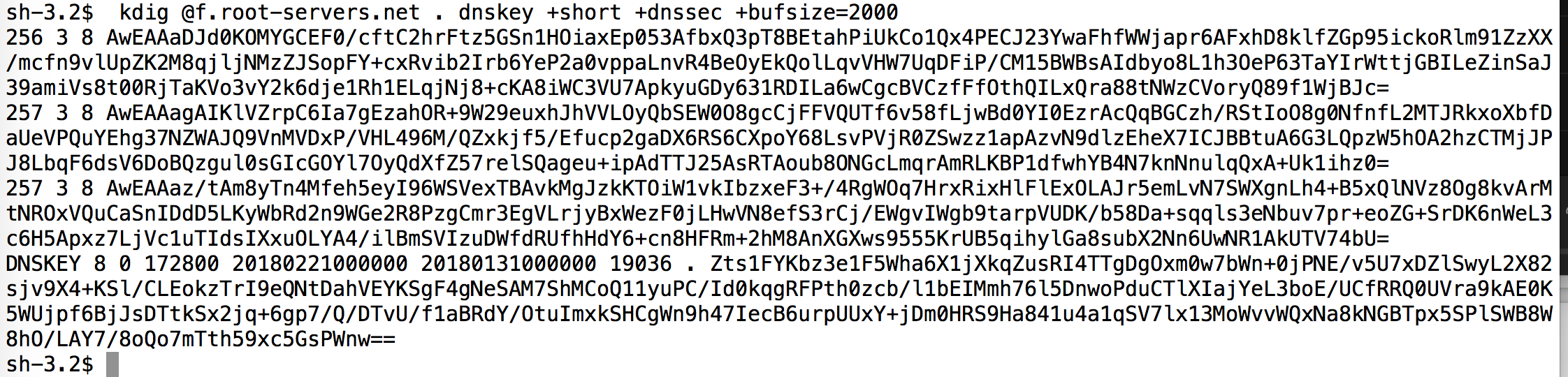

You can query for the DNSSEC signature (the RRSIG record) of “www.cloudflare.com” using your friendly dig command.

$ dig www.cloudflare.com +dnssec

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;www.cloudflare.com. IN A

;; ANSWER SECTION:

www.cloudflare.com. 4 IN A 198.41.215.162

www.cloudflare.com. 4 IN A 198.41.214.162

www.cloudflare.com. 4 IN RRSIG A 13 3 5 20180207170906 20180205150906 35273 cloudflare.com. 4W4mJXJRnd/wHnDyNo5minGvZY6hVNSXITnUI+pO6fzhnkpsEp1ko8K7 1PQ6r0s9SwLgrgfneqXyPs4b5X0YDw==

The two A records shown here can be cryptographically verified using the RRSIG and ZSK in the zone. The ZSK can itself be verified using the KSK, and so on… this continues upwards following the “chain of trust” until the root KSK is found.

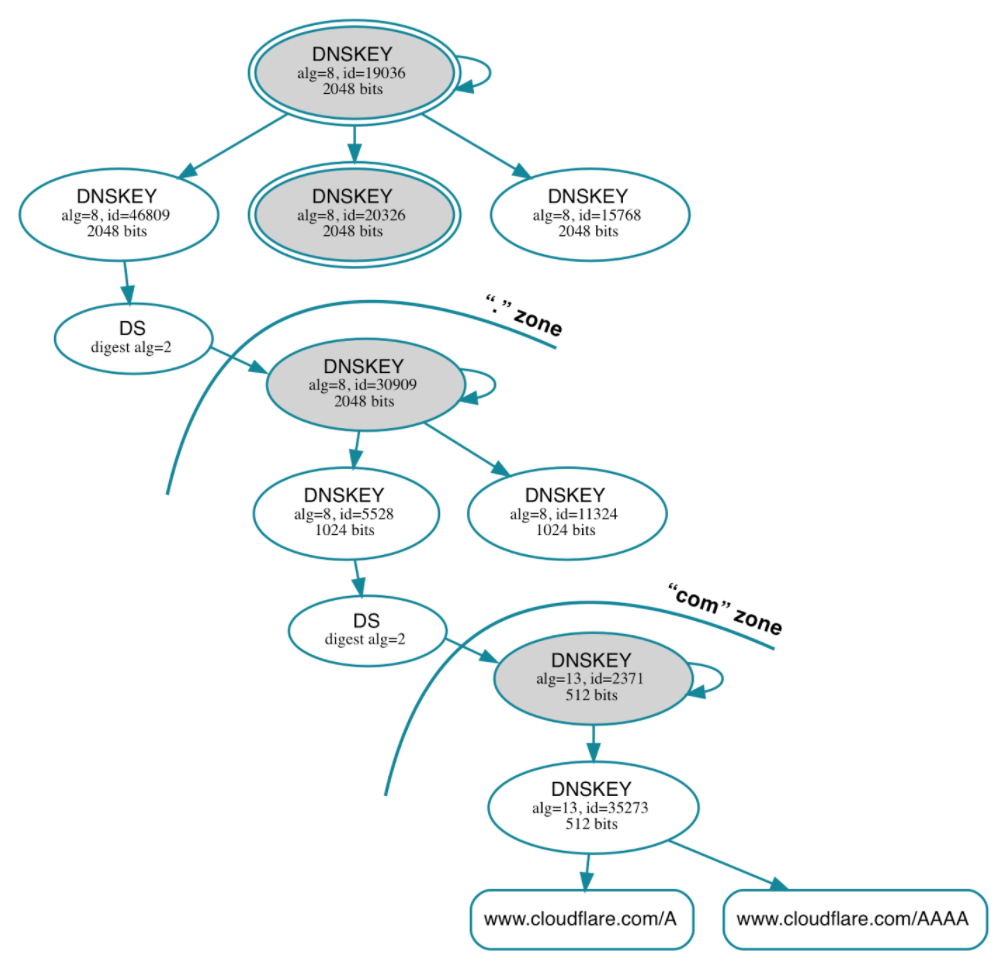

The http://dnsviz.net/ tool can be used to help visualize how this verification can be done for any domain on the internet, for example here is the trust chain for “www.cloudflare.com”.

To verify the RRSIG on “www.cloudflare.com” we would need to cryptographically verify the signatures in reverse order on the diagram. First “cloudflare.com”, then “com”, and finally “.” – the root zone.

If you are able to access the secret key that’s used to sign the root, it’s possible to trick resolvers into verifying a "forged" answer.

While this DNSSEC signing has been deployed on the root zone, for over seven years, there is one operation that has never been attempted: rolling the Key Signing Key. This means to generate a new key and update every part of DNS infrastructure on the internet that needs it, retiring the old one completely.

The ZSK (Zone Signing Key) has been rolled religiously every quarter since 2010, however rolling the Key Signing Key is a much scarier operation. If it goes wrong it could leave the root zone signing invalid, meaning a large part of the internet would not trust any of the content, effectively knocking DNS offline for validating resolvers. After DNSSEC was designed, a mechanism was devised for rolling out a new Key Signing Key in RFC5011, this operation is commonly known as the 5011 roll-over.

What is a KEY rollover?

All cryptographic keys have a life cycle that can represented by states:

Generated == the key is created but only the “owner” knows of its properties.

Published == the key has been made public either as a public key or a hash of it.

Active == the key is in use

Retired == the has been withdrawn from service but is still published

Revoked == they key has been marked as not to be trusted ever again.

Removed == taken out of publication

Different keys move through the states in different ways depending on the usage, for example some keys are never revoked, just removing them is sufficient, for example the root ZSK’s are never revoked. When rolled, the root KSK will pass through all states.

Why is the Root KSK different ?

For most keys used in DNS the trust is derived by a relationship between the parent zone and the child zone. The parent publishes a special record, the DS (Delegation Signer), that contains cryptographically strong binding to the actual key, a hash. The child has a DNSKEY RRset at the top of its zone that has at least one key that matches one of the DS records in the parent. To complete the chain of trust the DNSKEY RRset MUST be signed by that key.

The root zone has no parent, thus trust cannot be derived in the same way. Instead, validating resolvers must be configured with the root Trust Anchor. This anchor must be refreshed during a key rollover or the validating resolver will not trust anything it sees in the root zone after the old KSK (from 2010) is retired from service. The Trust Anchors can be updated in a number of ways, such as a manual update, a software update, or an in-band update. The preferred update mechanism is the previously mentioned in-band update mechanism RFC5011-roll.

The process outlined in RFC 5011 relies on two factors, first that the new key is published in the DNSKEY RRset – which is signed by the old KSK, and is kept there for at least a hold-down period of 30 days. Validating resolvers that follow the procedure will check frequently to see if there is a new KSK in the DNSKEY set. The new key can be trusted because it has been signed with a key that is already in service. When there is new key, it is placed in PendingAddition state If at any point one of the key’s in PendingAddition is removed from the DNSKEY set, the resolver will forget about it. This means that if the key were to appear again, it would start a new 30 day hold-down period.

After the key has been in PendingAddtional for 30 consecutive days it is accepted into Active state and will be trusted to sign the DNSKEY set for the root. From this point onwards, the new key can be used to sign the Zone Signing Key, and in turn the root zone content itself.

Why are we rolling the root key trust anchor?

There are two main reasons;

- The community wants to be a sure that the RFC5011 mechanism works in practice. Knowing this makes future rollovers possible, and less risky. Regular rollovers are something to be done as a matter of good key hygiene, like changing your password regularly

- Enables thinking about switching to different algorithms. RSA with a large key size is a strong algorithm, but using it causes DNS packets to be larger. There are other algorithms like the ones that Cloudflare uses that are based on elliptic curves have smaller keys but increased safety per bit. To switch to a new algorithm would require a new key.

Some people advocated rolling the key and changing the algorithm at the same time but that was deemed too risky. The right time to start talking about that is after the current roll concludes successfully.

What has happened so far?

ICANN started the rollover process last year. The new keys has been created and replicated to all the HSM’s (Hardware Security Modules) in the two facilities that ICANN operates. From now on we will use the terms KSK2010 (the old key) and KSK2017 (the new key).

Before starting the roll-over process, testing of RFC5011 implementations took place and most implementations reported success.

The new key was published in DNS on July 11th 2017, thus the DNSKEY set now contains two KSKs. At that point the new key/KSK2017 has entered Published state. It was scheduled to become Active on October 11th 2017. Any validating resolver that has been operating for at least 30 days during the July 11-October 11 window should have placed the new Trust Anchor in “Active” state before October 11th. But sometimes things do not go according to plan.

One of the things that was put in place before the rollover was a way for resolvers to signal to authoritative servers what trust anchor the resolver trusts RFC8145. RFC8145 was only published in April 2017, thus during the KSK2017 key publication phase, only the latest version of Bind-9 supported it by default.

The mechanism works by resolvers periodically sending a query to the root nodes, with a query name formatted like “_ta-4a5c” or “_ta-4a5c-4f66”. The name contains HEX encoded versions of the Trust Anchor identifiers, 19036 and 20326 respectively. This at least allows root operators to estimate the % of resolvers that have implemented RFC8145 AND are aware of each Trust Anchor.

On September 29 ICANN postponed the roll based on evidence from the resolvers that sent in reports.

It was concerning that the latest and greatest version of Bind-9 in 4% of cases did not pick up the new Trust Anchor, this was explained in more detail in a DNS-OARC presentation. But this still leaves us with the question, why?

It is also important to note that although other implementations of RFC8145 did not enable it by default thus most of the reports were by Bind-9.

Rolling the KSK at this point would have resulted in the remaining resolvers not trusting the content of the root zone, ultimately breaking all DNS resolution through them.

Operational reality vs the protocol design

At Cloudflare we operate validating resolvers in all of our >120 data centers, and we monitored the adoption of trust anchors on a weekly basis, expecting everything to work correctly. After 6 weeks we noticed that things were not going right, some of the resolvers had picked up the new trust anchor and others had not accepted the new trust anchor even though more than enough time had passed.

First let’s look at the assumptions that RFC5011 makes.

- The resolver is a long running process that understands time and and can keep state

- The resolver has access to persistent writeable storage that will work across reboots.

In the protocol community we had worried about the first one a lot, for the second one we had identified two failure cases: machine configured from old read-only medium, and new machine takes over. Both were considered rare enough and operators would know to deal with those exceptions.

Turns out the second assumption in RFC5011 had more failure modes than the community expected.

For example in Bind-9, it originally had a hardcoded list of “trusted-keys”. Later when RFC5011 support was added the configuration option “managed-keys” was added. It looks like some installations while religiously updating the software never changed from the fixed configuration to the RFC5011 managed one. In this case the only recovery is to change the configuration, and in some cases the operator selected this operating mode assuming he/she would distribute a new configuration file during rollover, but the person may have left or forgotten.

Software that uses managed-keys operations (Bind-9, Unbound, Knot-resolver) uses a file to maintain state between restarts. BUT it is possible that the file is read-only and in that case managed-keys works just like trusted-keys. Why anyone would have a configuration like that is a good question? The interesting obersevation is that unless the implementation complains loudly about the read-only state, the operator is not likely to notice. The only recovery option here is to change the configuration so the trust anchor file can be written.

Software upgrades are another possible reason for not picking up the new trust anchor, but only if the file containing the Trust Anchor state is overwritten or lost. This can happen if the resolver machine has a disk replacement/reformat etc. but in this case the net effect is only slowing down the acceptance of the new trust anchor. This failure is visible as as KSK2017 spends more than 30 days in state “PendingAddition” but that is only visible if someone is looking.

Modern operating practices use “containers” that are spun up and down, in those cases there is no “persistent” storage. To avoid validation errors in this case the software installed must know about the new key or perform a key discovery upon startup like the unbound-anchor program performs for Unbound.

There are probably few other reasons where operations may cause the errors seen by the Trust Anchor Signaling.

Back to what happened at Cloudflare? In our case the issue was a combination of upgrades and container issues. We were upgrading software on all our nodes and our resolver processes were allocated to different computers. Our fix was to quickly upgrade to a software version that knew about the new trust anchor, so future restarts/migrations would not cause loss in trust.

What is next for the KSK rollover

ICANN has just asked for comments on restarting the rollover process and perform the roll on October 11th 2018.

What can you do to prepare for the key rollover?

If you operate a validating resolver, make sure you have the latest version of your vendors software, audit the configuration files and file permissions and check that your software supports both KSK2010 (key tag 19036) and KSK2017 (key tag 20326).

If you are a concerned end user right now there is nothing you can do, but the IETF is considering a proposal to allow remote trust anchor checking via queries. Hopefully this will be standardized soon and DNS resolver software vendors add support, but until then there is no testing possible by you.

If you speak languages other than English and you worry about your local operators should know about the DNSSEC Key Rollover failure modes, feel free to republish this blog or parts of it in your language.

HSM destruction at the next KSK ceremony Feb 7th 2018

Every quarter there is a new KSK signing ceremony where signatures for 3 months of use of the KSK are generated. February 6th 2018 is the next one and it will sign a DNSKEY set with both KSKs but only signed by KSK2010 . You can see the script for the ceremony here and you can even watch it online. But the fun part of this particular ceremony is the destruction of old HSM (Hardware Security Module), via some fancy contraption.

An HSM is a special kind of equipment that can store private keys and never leak them, and protects its secrets by erasing them when someone tries to access/tamper with the equipment. The secrets remain in the HSM as long as a non-replaceable battery lasts. The old KSK HSMs have a lifetime of 10 years and were made in late 2009 or early 2010 thus the battery is not designed to last much longer. Last year the private keys were safely and securly moved to newer models and the new machines have been in use for about a year. The final step of retiring the old machines is to destroy them during the ceremony, tune in to see how that is done.

Excited by working on cutting edge stuff? Or building systems at a scale where once-in-a-decade problems can get triggered every day? Then join our team.